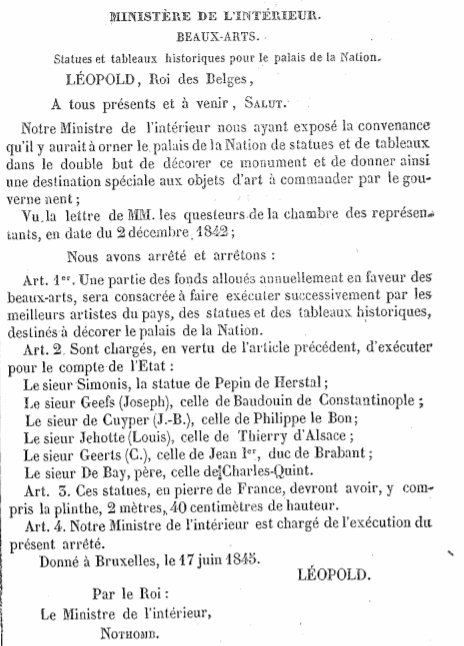

The statues of the Palace of the Nation peristyle

Niches depressingly empty... finally filled

After the United Kingdom of the Netherlands was created in 1815, the current Belgian Parliament building, formerly the seat of the Council of Brabant (a court of justice) was transformed to house the States-General, the legislature for all the provincial states. Architect Charles Van der Straeten undertook the modifications needed so that the First and Second legislatures could meet in Brussels (at that time, the sessions alternated between Brussels and the Hague).

The vast entrance lobby (today referred to as the 'peristyle') was gradually fitted out with two grand staircases, Doric columns and six niches for statues.

The sculptor Gilles-Lambert Godecharle (1750-1835), who had already undertaken the relief on the pediment of the building, was commissioned in 1817 to produce statues of six historical figures. The figures selected combined the United Provinces and the Southern Netherlands, since they included William of Orange-Nassau (William the Silent), the Count of Egmont, Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, Admirals Cornelis Tromp and Michiel De Ruyter, and finally Philip of Marnix de Sainte-Aldegonde. Godecharle submitted models in May 1818, but William I apparently did not feel it would be appropriate to commission them. Following the fire in 1820, the architect again raised the question of the statues, but the Sovereign remained intransigent. The six niches therefore remained empty.[ 1 ]

Almost 25 years later, Jean-Baptiste Nothomb, then head of government and Minister for the Interior of the Kingdom of Belgium, wanted to give more effective direction to the purchase of art works by the young Belgian State. First, he wanted a programme to be established for decoration of the Palace of the Nation. In a letter addressed to the House Quaestors, he suggested to them that they provide him with a preliminary plan of the locations in the Palace of Nations where art works could be placed; he proposed that 20,000-25,000 Belgian francs a year be devoted to this for a certain number of years.

The Quaestors, who passed the empty niches in the peristyle every day, suggested that priority should be given to finally adding statues to them. In their enthusiasm, they also proposed that two 'lions couchant' be placed at the foot of the stairs leading to the House and the Senate and that eight busts be placed against the columns of the peristyle. Nothomb paid no heed to this! He did, however, commission, by Royal Decree of 17 June 1845, the six statues that we can still see today... or almost.[ 2 ]

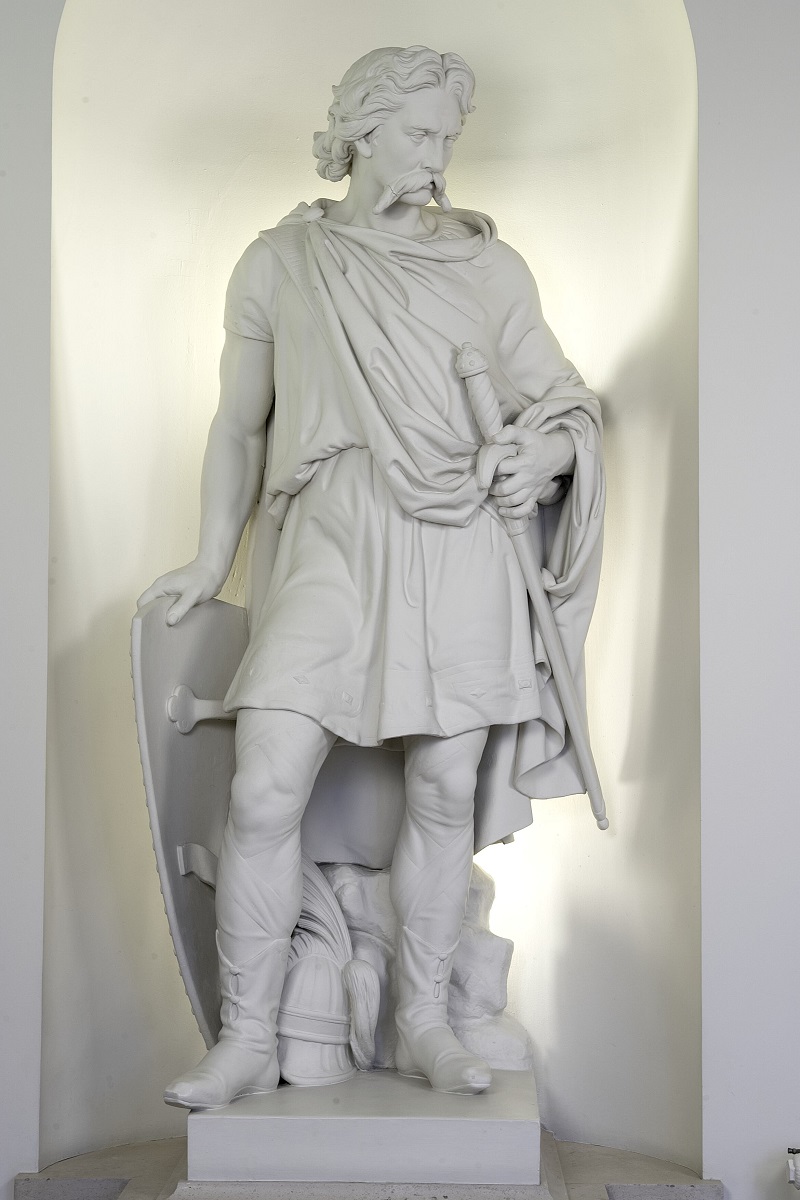

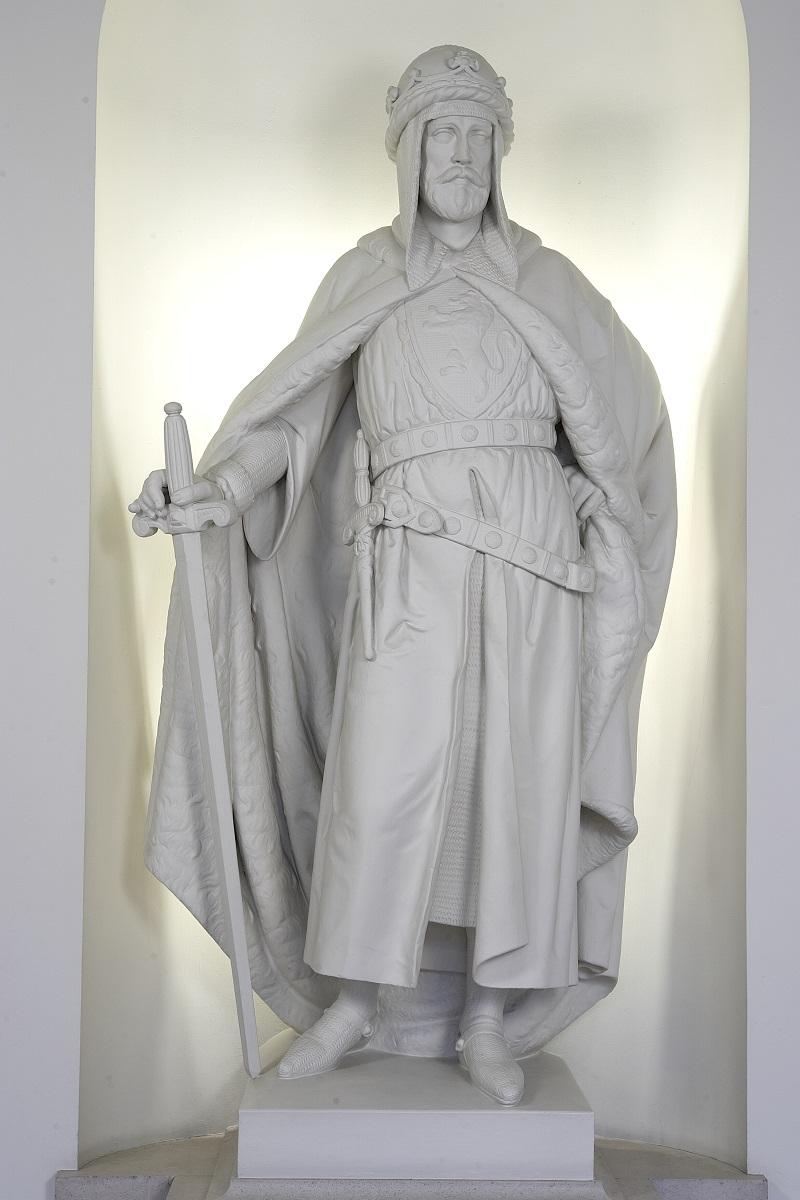

Under the Decree, each statue was assigned to a different sculptor and the statues were to be produced in French stone (Pierre de France) and be 2m 40cm in height. The signatures can still be made out on the plinths of the statues (on the lateral side on the left). Louis-Eugène Simonis was commissioned to produce the statue of Pepin of Herstal; Louis Jehotte to do that of Thierry of Alsace; Joseph Geefs was assigned that of Baldwin of Constantinople. These were placed on the Senate side.

Photo © KIK-IRPA, Brussels

Photo © KIK-IRPA, Brussels

Photo © KIK-IRPA, Brussels

On the House side, we find John I of Brabant, sculpted by Karel Geerts, Phillip the Good by Jean-Baptiste De Cuyper and Charles V by Jean-Baptiste-Joseph De Bay the Elder.[ 3 ]

Fire of 1883 and restoration of the statues

In December 1883, a major fire broke out in the plenary session room of the House of Representatives, devastating it. Floors in the adjacent rooms were also damaged, including the House reading room just above the peristyle, which collapsed into the main entrance lobby.

On a photo taken by photographer Alexandre just after the fire, the peristyle opposite the statues on the Senate side is flooded, strewn with debris and seems to be black with soot. Just beyond the statues, one can see part of a Doric column, towards the House, and the ceilings and floor that have collapsed.

But the statues themselves seem to have been relatively untouched, probably protected by their niches. The more fragile and salient features, such as the sword of Thierry of Alsace or the sceptre of Baldwin of Constantinople, are still clearly present. The same is true of the chandelier that lit the central part of the peristyle on the Senate side.

It is difficult to get a true idea of the situation on the House side since there are no photos, but the fire had certainly raged there more fiercely than on the Senate side (its own hemicycle was not touched, in contrast to the smoking room, reading room and current Green Lounge, then the Senators’ cloakroom.

In June 1886, sculptor Edmond Lefever (1839-1911) finished restoring the statues and was paid 2,700 Belgian francs by way of a 'third and last instalment'.[ 5 ]

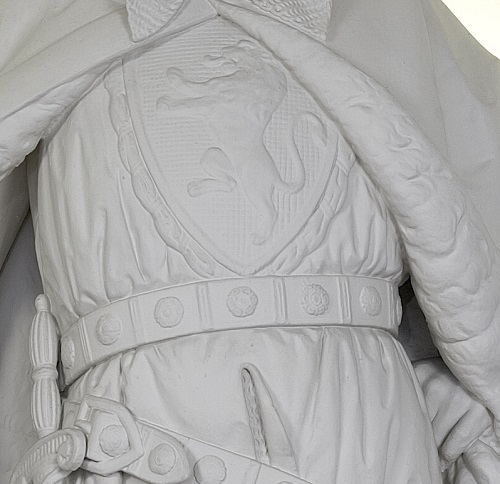

Today, the statues are covered with a relatively thick layer of white paint. This has led art historians to question the scale of the restoration undertaken by Edmond Lefever.

Were the statues so damaged by the fire that they had to be totally overmoulded, as claimed by Chantal Jordens-Leroy in her study on Simonis? 'The six heavily damaged statues were restored. Given their current state, it is probable that they were overmoulded from the fragmented remains of the originals that were still standing. Today, the niches just contain painted plaster statues - originally in French stone - the ponderousness and fuzziness of which cannot entirely be attributed to the artists who created them. The statue of Pepin of Herstal has little to recommend it. The anatomical construction shows signs of ineptitude; the draped cloth, of which Simonis was a master, are paltry and the work is sloppy in terms of the details; the borders on the clothing, the decoration on the arms, are barely discernible and, moreover, follow the same model for all six statues'.[ 6 ]

Were they really totally redone? Or were faults repaired and the statues painted after the fire, originally using lime paint to disguise the traces of smoke, soot and water?

In his account, Lefever states that the work indeed involved 'the restoration and return of the six statues to their places'. Of note is the term 'restoration' and the fact that the 'statues' were returned to their places, not moulds or plaster models.

Given that Lefever was paid 2,700 Belgian francs on three occasions, this would have made a sum total of 8,100 for all the statues. This amounts to 1,350 Belgian francs per statue, including returning them to their respective places.[ 7 ] This would seem quite a low figure for full remoulding, with all the details on all six statues having to be chiselled out again.

Furthermore, had they been remoulded, which would have involved making a mould from the damaged authentic stone statues, then pouring plaster into the moulds to create new statues, the details on the surface could indeed become 'fuzzy'. But the statues would then have been entirely of plaster, including those parts at the back that were not sculpted, and even the backs of the pedestals (which, based on the order placed, formed an integral part of the statues). However, when the surfaces of the statues on the Senate side were restored in 2017,[ 8 ] this brought to light the fact that there was, in fact, stone beneath the layers of paint - a darker stone that glitters here and there at the back of the pedestals and at the back of certain statues.[ 9 ]

Finally, better lighting, more oblique than the current back-lighting, makes it possible to rediscover all the details... notwithstanding a degree of thickening due to the successive layers of paint applied over the years. This closer look argues in favour of the artists who produced the statues.

The hand of Simonis can therefore be clearly seen in the drapes with which Pepin of Herstal is adorned. Compared with its fellows in their niches, the drapes are indeed of a quality that is distinctly superior. But the details of the clothing of Thierry of Alsace and Baldwin of Constantinople are also well worth a look.

- Luc Somerhausen and Willy Van den Steene, Le Palais de la Nation (Palace of the Nation), Brussels, 1981, pp. 145, 159-160. The grand staircase leading to the Senate was not erected until after the fire in 1820. Up to that time, the Prince of Orange had occupied the room on the Senate side, which had prevented any staircase from being built. William I had been opposed to filling the niches on the Senate side with statues for exactly the same reason. [ back ]

- Nothomb resigned on 30 July 1845: had it been a few weeks earlier, those statues, in their turn, would not have seen the light of day! [ back ]

- No-one knows who drew up the historical programme of statues for Nothomb. Might it already have been Joseph Kervyn de Lettenhove [1817-1891], who was at that time a young historian immersed in the history of our regions, and who would later suggest a somewhat similar, but more comprehensive, programme for the Senate plenary chamber in 1863? [ back ]

- F. Livrauw, La Chambre des Représentants en 1894-1895 (The House of Representatives in 1894-1895), pp. 445-446. [ back ]

- General Archives of the Kingdom, Ministry of Public Works, Civic Buildings, file 64. We owe to Lever the historical statues on the façade of the Brussels Town Hall, in the Petit Sablon in Brussels, in the Ypres Cloth Hall, etc. [ back ]

- JORDENS-LEROY Chantal, Un sculpteur belge du XIXe siècle: Louis-Eugène Simonis (A Belgian sculptor of the 19th century: Louis-Eugene Simonis), Brussel, Belgian Royal Academy, 1990, pp. 90-91: "Les six statues durement endommagées furent restaurées. Au vu de leur état actuel, il est plus probable qu'elles furent surmoulées à partir de fragments originaux encore disponibles. Aujourd'hui, les niches ne contiennent plus que des statues en plâtre peint – elles étaient en pierre de France – dont la lourdeur et la mollesse ne peuvent être imputées entièrement aux artistes créateurs. Le Pépin de Herstal a peu d'attrait. Il y a des maladresses dans la construction anatomique; les drapés où Simonis se montre tellement supérieur, sont ici insignifiants et le travail est bâclé quant au rendu des détails; les borderies des vêtements, le décor des armes, sont à peine indiqués et par ailleurs, faits sur le même modèle pour les six statues." [ back ]

- By way of comparison, the painter Gallait was paid 6,000 Belgian francs per portrait for the Senate gallery. [ back ]

- Senate, file on the restoration, in 2017, of the statues of Pépin of Herstal, Thierry of Alsace and Baldwin of Constantinople, by Jacques Vereecke with the assistance of Cécile van Seymortier. [ back ]

- As the statues were removed for restoration by Lefever, it is possible that they were covered in their entirety, including the back, in a layer of lime paint. But when they were repainted (on many occasions during the 20th century), the back would have been far less accessible. The layers of paint are therefore much less thick in places, particularly on the pedestals, and the original stone shows through. [ back ]

© Belgian Senate