Louis Gallait and the plenary room of the Senate of Belgium

Empty and cold...

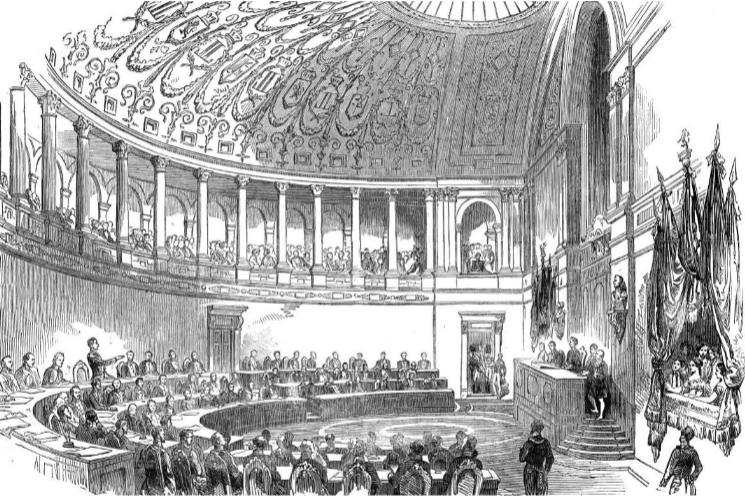

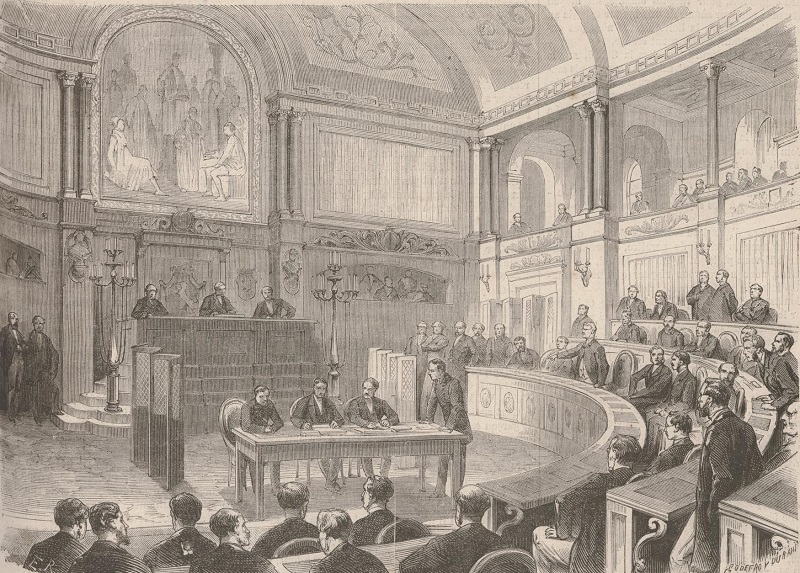

When Parliament reopened in 1849, the Belgian Senate assembled for the first time in its new 'debating chamber'.

Still very 'bare', the room did not yet have mahogany panelling around the outside of the hemicycle and, while the dome had been sculpted and decorated with the coats of arms of the provinces, it was still entirely white. At the front, behind the presidential platform, the coats of arms of Belgium had been mounted, as had the busts of the sovereigns. High up, three spaces had been set aside for paintings. But they were still empty.

In September 1853, a large allegorical canvas entitled 'La Belgique fondant la monarchie' (Belgium establishing the monarchy) was mounted in the central space.[ 1 ] Clearly, it added little warmth to the atmosphere since a critic of that time said of it, 'Never has a painting been more glacially official'![ 2 ] The Senators, who had demanded that Edouard de Biefve (1808-1882) produce this canvas, did not dare to make much of a fuss... But when, a few years later, the painter offered to provide paintings for the two other empty spaces too, they politely declined his offer.

In 1863-1864, the dome was gilded and colour was applied by the decorator Charle-Albert, while the master cabinetmaking firm Leopold De Meuter & Fils delivered the first of the mahogany panelling for the walls of the plenary room. This panelling included spaces for paintings. In 1859, the Minister of the Interior, Charles Rogier, urged the Senators to appoint the painter Louis Gallait (1810-1887) to produce them, his aim being to tempt this painter back to Belgium by awarding him assignments; Gallait, at that time a highly renowned history painter, spent most of his time living in Paris. In May 1863, Baron Misson, Greffier of the Senate, placed an order with Gallait for 15 full-length portraits.

The historical portraits of Louis Gallait

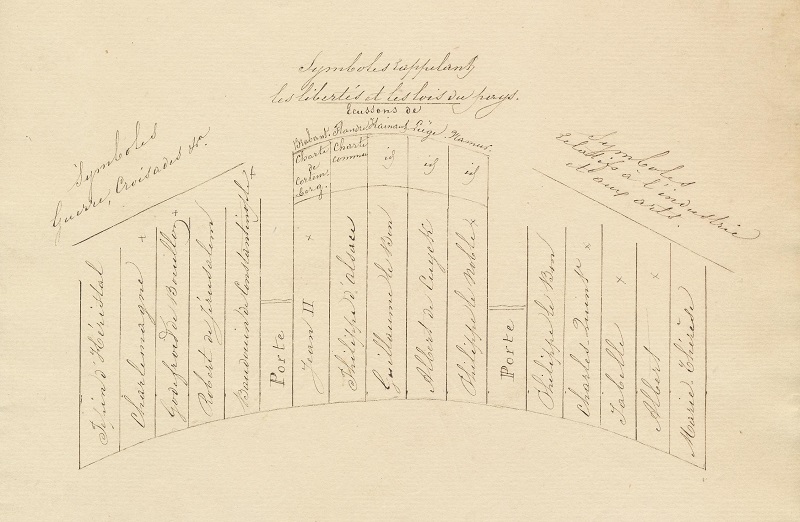

The initial programme of portraits, suggested by historian Kervyn de Lettenhove, a member of the House of Representatives, underwent several changes over time, making them slightly less legible today.[ 3 ]

On the left were Pepin of Herstal, Charlemagne, Godfrey of Bouillon, Robert of Jerusalem and Baldwin of Constantinople, who, from the outset, formed the group representing 'symbols of war and of the crusades'.

Following extension of the room in 1904 and the relocation of the doors, they were however joined by the cleric Notker of Liege.

While Notker found himself in the first group of 'crusader warriors' 'by architectural accident', he would not have been any more at home among the figures in the central group. The reason he was there was that the Senators had chosen him to replace Albert de Cuyck, the figure that Kervyn had proposed to represent Liege in the central series of 'lawmaker-princes'. First as bishop (972), then prince-bishop of the Principality of Liege (980), Notker certainly oversaw a major expansion of Liege, in particular of the town's urban fabric, its fortifications, commerce and teaching, to the point where, under his reign, Liege was referred to as the 'Athens of the North' and a poet of that time said: 'Liege, you owe Notker to Christ and the rest to Notker'.[ 4 ] Hoewel Notger dus door "architecturale toevalligheid" in de eerste groep van de "strijders-kruisvaarders" terechtkomt, is hij evenmin echt op zijn plaats tussen de personages van de centrale groep. Hij bevindt zich daar omdat hij, op initiatief van de senatoren, het personage vervangt dat Kervyn had gekozen om Luik te vertegenwoordigen in de centrale reeks "prinsen-wetgevers". Notger was achtereenvolgens bisschop (972) en prins-bisschop van het Prinsdom Luik (980) en zorgde ervoor dat Luik sterk tot ontwikkeling kwam, in het bijzonder het stadsweefsel, de vestingwerken, de handel en het onderwijs, in die mate dat Luik onder zijn bewind "het Athene van het Noorden" werd genoemd. Een dichter uit die tijd zei: "Luik, je hebt Notger aan Christus te danken en de rest aan Notger."[ 4 ]

But it could not be said that he was a 'lawmaker-prince'. In contrast, Albert de Cuyck, also a prince-bishop, was the author of a charter (the Liege 'magna carta' of 1196) that confirmed the privileges of the towns and municipalities in our regions, along with John II of Brabant, Philip of Alsace, William the Good and Philip the Noble, justifiably formed part of the gallery of 'lawmaker princes' of Brabant, Flanders, Hainaut, Namur and Liege.

Kervyn, although a Catholic, wanted their presence to 'serve as a solemn reminder of just how longstanding liberty was in Belgium'.[ 5 ] This was certainly appreciated by the Presidents of the Senate, all of whom were Liberals from 1848 to 1884! In addition, the shields of these lawmaker-princes mirrored the coats of arms of Belgium sculptured behind the presidential platform, while facing the President was Jean II, Duke of Brabant, displaying the Charter of Kortenberg,[ 6 ] seen as the precursor to the Belgian constitution.

Photo circa 1945, © KIK-IRPA, Brussels

Duke of Brabant. Circa 1873.

Photo © KIK-IRPA, Brussels

These lawmaker-princes are currently in the company of Philip the Good, even though the latter - like Charles V, the Archduchess and Archduke Isabelle and Albert together with Empress Marie-Therese - belongs, to the group on the right, that of the 'symbols of the arts and industries' for Kervyn but, for the Senators, the group of 'protectors of the sciences, arts and letters'.

In 1863, Louis Gallait undertook to complete the portraits in three to four years. But he had greatly underestimated the research required to complete a series that was both faithful to history and aesthetically varied and animated. In his own words in 1872: 'The historical research for the facial features and costumes of the celebrated figures that I have to reproduce have called for serious study; then the composition of the fifteen portraits, all from different eras, which must vary in their poses and arrangement, has required relatively long preparatory work'[ 7 ] But this work was finally completed...

On 14 November 1873, King Leopold II came to see the sketches at the Senate. Gallait was able to produce black and white sketches and miniatures of the future full-length portraits. Likely quite impressed, Leopold II asked to have the miniatures for the Palace, where they are still displayed in a prominent place.

In March 1872, Gallait informed the Senators, who were close to despair, that he hoped to have finished the first portrait by summer 1873... It would be that of John II, Duke of Brabant, to be placed opposite the presidential platform.

He then went on to deliver six portraits, Pepin, Robert of Jerusalem, Baldwin of Constantinople, Notker, William the Good and Philip the Noble, in 1878. The others undoubtedly followed in 1879.[ 8 ]

Delighted with Gallait's work, the Senators then commissioned from him portraits of the sovereigns and their spouses, in order to complete the series. They were to be placed either side of Edouard de Biefve's painting.

But ten years later, with the death of Louis Gallait in November 1887, only the portraits of King Leopold I and Queen Louise-Marie had been finished. The portrait of Queen Marie-Henriette was in the process of completion. That of Leopold II and the central panel representing an allegory of the swearing in of Leopold I, were still just sketches. The project was abandoned. The finished portraits of Leopold I and Louise-Marie were hung next to the painting by de Biefve, while the frames, which had already been installed, for the portraits not completed were removed.[ 9 ]

Charles of Lorraine and Marie-Christine

When the plenary room was enlarged at the beginning of the 20th century, the Senate commissioned two additional portraits for its hemicycle. After long reflection and consultation, since there were plenty of figures to choose from (Ambiorix, Boduognatus, Julius Caesar, Clovis, one of the many Belgian evangelist saints, Jacob van Artevelde, Margaret of Austria, Cardinal Granvelle or even Joseph II or the lawyer Henri van der Noot), ultimately Charles of Lorraine and Marie-Christine won the day.

Alfred Cluysenaar (1837-1902) was commissioned for the work on 18 November 1902, but died 4 days later! André Hennebicq (1836-1904) then took up the baton to produce a portrait of Charles of Lorraine in the style of Gallait, hung in the hemicycle in 1904, before he, in turn, died. The portrait of the Archduchess Marie-Christine was finally painted by Julian Devriendt (1842-1935), the then Director of the Fine Arts Academy in Antwerp: the sketch was presented in November 1905 and the portrait was paid for in that same year.[ 10 ]

- All trace was lost of this painting by Edouard de Biefve, a history painter very much in favour at the time, after it was taken down in 1896 to be replaced by Jacques de Lalaing's 'historical fresco'. Preparatory drawings are held at the Royal Library of Belgium (KBR), Prints Room. Some of them are reproduced in the study by Judith Ogonovsky, 'Eduoard de Biefve (1808-1882). Une étoile filante au sein de l'art officiel belge', in Revue belge d'archéologie et d'histoire de l'art, no. 71, 2002, pp. 59-88. [ back ]

- Lucien Solvay, 'Notice sur Edouard de Biefve, correspondant de l'Académie', in Annuaire de l'Académie royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, 1915-1919, p. 68. [ back ]

- Archives of the Belgian Senate, 'The Gallait paintings', letter from Baron Kervyn de Lettenhove to the Clerk of the Senate, Baron Misson, of 20 April 1863. [ back ]

- See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Notker_of_Liège [ back ]

- Belgian Senate archives, 'The Gallait paintings' file, letter from Baron Kervyn de Lettenhove to the Greffier of the Senate, Baron Misson, of 20 April 1863. [ back ]

- It is not for nothing that there is an Avenue de Cortenbergh/Kortenberglaan in Brussels... [ back ]

- Belgian Senate archives, 'The Gallait paintings' file, letter from Louis Gallait to the President and members of the Senate of 16 March 1872. 'The historical research for the facial features and costumes of the celebrated figures that I have to reproduce have called for serious study; then the composition of the fifteen portraits, all from different eras, which must vary in their poses and arrangement, has required relatively long preparatory work'. [ back ]

- This is, in any event, what Victor Champier claims in 'L’année artistique 1878', L'Année artistique: beaux-arts en France et à l'étranger, Paris, (1878), p. 438. The Senate archives show that payments continued until July 1879. [ back ]

- Belgian National Archives, Archives of the Ministry of Public Works, Civic Buildings, file no. 70. The portraits of Leopold I and Louise-Marie were presented to the Belgian State in 1895, at the same time as the canvas by Edouard de Biefve. Senate archives, 'de Biefve' file, letter from the Quaestors to the Minister for Agriculture of 26 December 1895. [ back ]

- Senate archives, the 'Cluysenaar', 'Hennebicq' and 'Devriendt' files. [ back ]

© Belgian Senate